Visit Green Cubes at HIMSS Global Health Conference & Exhibition 2026, Las Vegas, NV March 9-12,

On December 16, 1894, W.W. Gibbs, President of the Electric Storage Battery Company (ESBC) made a stunning announcement. Gibbs, who founded ESBC in 1888, asserted that he had just purchased all the patents and rights necessary to make ESBC the sole supplier of electric storage batteries in the United States. These patents were purchased from the General Electric Company, the Edison company, the Thomson-Houston, the Brush, the Accumulator company, the Consolidated Electric Storage Company and the General Electric Launch Company. Whether or not he actually had a monopoly is beside the point. Over the next hundred years, ESBC continued a relentless series of mergers and acquisitions to remain one of the largest manufacturers and recyclers of lead acid batteries in the world. Known today as Exide Technologies, the company would have you believe that their “closed loop recycling process” (cleverly dubbed Total Battery Management by their marketing department) recovers 99% of lead and is a safe and sustainable form of energy storage and motive power.

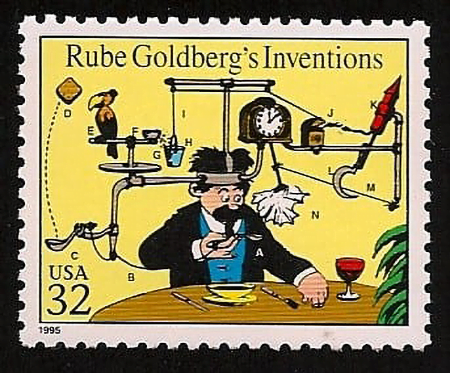

If he were alive today, I imagine Rube Goldberg would find Exide ripe for satire. Goldberg, who was five years old when W.W. Gibbs started ESBC, was an American cartoonist best known for depicting gadgets that performed simple tasks in overly complicated ways. For instance, in his classic 1931 comic entitled Professor Butts and the Self-Operating Napkin, Goldberg shows a gentleman eating soup with an outlandish contraption strapped to his head and arms. When he lifts the spoon to his mouth, a string tied to his elbow jerks a ladle which flings a cracker past a toucan perched above the professor’s head. When the toucan jumps for the cracker, seeds are dumped into a pail, pulling a cord which ignites a lighter, setting off a rocket attached to a sickle, which cuts a string allowing a pendulum to swing back and forth thus wiping the professor’s chin. Rube Goldberg’s machines skewered our proclivity for the blind use of technology. Why do we expend such vast resources and cause such great damage in exchange for such paltry returns?

Why indeed?

Lead is a heavy metal, and exposure to even small amounts of it poses significant health risks. Lead poisoning is irreversible and there is no cure. Children are most susceptible, and even low levels of exposure can cause reduced IQs, learning disabilities and developmental problems. High levels of exposure can cause mental retardation, comas, convulsions, and death. Once we became aware of the real and serious hazards of lead, we took concrete steps to remove it from our surroundings. Since 1977, lead has been banned in paint used in all residential and public properties. We’ve also reduced or removed lead from gasoline, electronics, and construction materials. But one very significant source of lead remains: lead acid batteries. According to the World Health Organization (WHO), today around 85% of the world’s lead consumption is for the production of lead acid batteries.

The fact is, lead acid battery power is neither safe nor sustainable, and when you begin to look at how complicated and dangerous the Total Battery Management system really is, the Rube Goldberg Machine begins to build itself. Even taken at face value – that 99% of lead is recovered in the recycling process – you’re still left with 1%. And after all, how bad could 1% really be? Just ask the residents of Vernon California.

A suburb of Los Angeles, Vernon was home to one of Exide’s lead acid battery recycling centers. Built in 1922, Exide took over operations in 2000. When it was operating, the lead acid smelter at the facility processed an average of 120,000 tons of lead – or approximately 11 million batteries – each year. Residents around the facility complained about the industrial pollution and the negative health impacts it had on the community. Over its last two decades of operation, regulators issued nearly 90 hazardous waste violations and sought to close the facility down, but Exide prevailed in the courts and continued to operate.

In 2013, Exide was forced to close the facility after admitting to illegally storing, disposing, and transporting hazardous waste for more than two decades. The California standard for lead in residential soil is 80 parts per million. Soil with lead above 1000 parts per million is considered hazardous waste. In 2008 lead levels in the soil around Exide were found to be 50 times the hazardous waste limit. In 2015, California’s Department of Toxic Substance Control announced that as many as 10,000 residential properties and as many as 100,000 residents may be have been affected. Now in the midst of the largest cleanup of its kind in California history, officials estimate costs could be in the hundreds of millions of dollars.

In 2020, Exide and four of its subsidiaries filed for Chapter 11 bankruptcy protection and sold substantially all its operating assets. Later that same year, a federal bankruptcy court allowed Exide to divest itself of responsibilities for multiple waste sites including Exide’s battery recycling plant in Vernon, CA. So far, Exide has avoided paying for any of the healthcare costs associated with their activities, and as long as they comply with the Federal agreement, they avoid criminal charges. But the residents of Vernon, as well as their lawyers, have not given up the fight to recover the damages Exide has caused to them, and their children, and their children’s children.

I imagine Mr. Goldberg would find great irony in a “Total Battery Management” system that was so outlandishly complicated and dangerous and provided such little value. Instead of toucans and rockets, he might depict battery change rooms and watering stations. Leaking acid might eat through strings and toxic fumes might turn large fans. Spent batteries might be flung into a smelter and “recycled” in order to perpetuate the machine, but the air, water, and soil would be damaged beyond repair. Maybe he could find humor in this “closed loop recycling system” whose very existence is predicated not on providing stored energy but rather in maintaining the status quo of a would-be monopoly hanging on to an outdated technology. And then perhaps Mr. Goldberg would be able to do what so many scientific studies, white papers, and peer-reviewed journals have failed to do: convince society that the time for lead acid batteries has passed. After all, how long will we continue to eat soup with toucans strapped to our heads before we realize there’s an easier way to wipe our chins?

DISCLAIMER Please note that everything posted on this site is up to date at the time of posting. Things change and products may be discontinued at any time. Please contact us for the most up to date information.